Late on the afternoon of Feb. 18, Vera Ares was at home in San Francisco when she received a phone call from her teenage son, Milo, who was in tears.

Her husband, 53-year-old career scientist Gustavo Pesce, and Milo had left home the day before for a trip to Bear Valley Ski Resort in the Sierra Nevada, 70 miles south of Lake Tahoe.

On a run down the resort’s terrain park, a collection of ramps, rails and icy features isolated from the main slopes, Pesce had inadvertently back-flipped on a ramp and landed on his chest. As he lay unresponsive in the snow, nearby skiers and snowboarders came to his aid, and the resort’s ski patrol rushed to administer CPR. But it was too late.

“He died within minutes,” Ares said.

Bear Valley managers told Ares all that they knew about the accident. She hoped the resort or local authorities would inspect the terrain park feature, called the Volcano, and follow up with her. But no new information ever emerged.

“It’s like it never happened,” Ares said. “There was nothing. No news.”

TC Connolly rides the Volcano feature at Bear Valley Ski Resort. The terrain park didn’t have the metal “bonk” feature protruding from the top in February when Gustavo Pesce fell on it.

Max Whittaker / The ChronicleThe accident at Bear Valley underscores a broader criticism of the U.S. snow sports industry: There is a lack of transparency about what occurs within the boundaries of the country’s 470 ski areas, which serve millions of visitors each winter.

The industry publishes safety guidelines, encourages guests to ski within their limits and releases macro statistics on injuries and fatalities each season. But individual ski areas are reluctant to divulge details of deaths and medical emergencies on their slopes.

Eventually Ares got the coroner’s report, which noted that her husband suffered blunt force trauma to his chest and a ruptured aorta. When she asked the Alpine County Sheriff’s Office whether there would be an investigation into the terrain park’s design or the resort’s safety protocols, she was told she’d need a court order.

“You just feel impotent, like there’s nothing you can do,” Ares said. “Nobody is paying attention to what’s happening at terrain parks and ski resorts.”

Bear Valley managers pride themselves on being “at the forefront” of terrain park design and safety, said resort director of operations Tim Schimke. Placards at the park’s entry gate caution that it is for expert skiers and snowboarders only. “If people don’t read them, unfortunately, that’s on them,” he said.

Amusement parks in some states, including California, are required by law to report injuries and deaths to regulators. No state, however, requires the same of ski areas, which have largely been left to devise their own safety protocols and handle medical care through their ski patrol divisions.

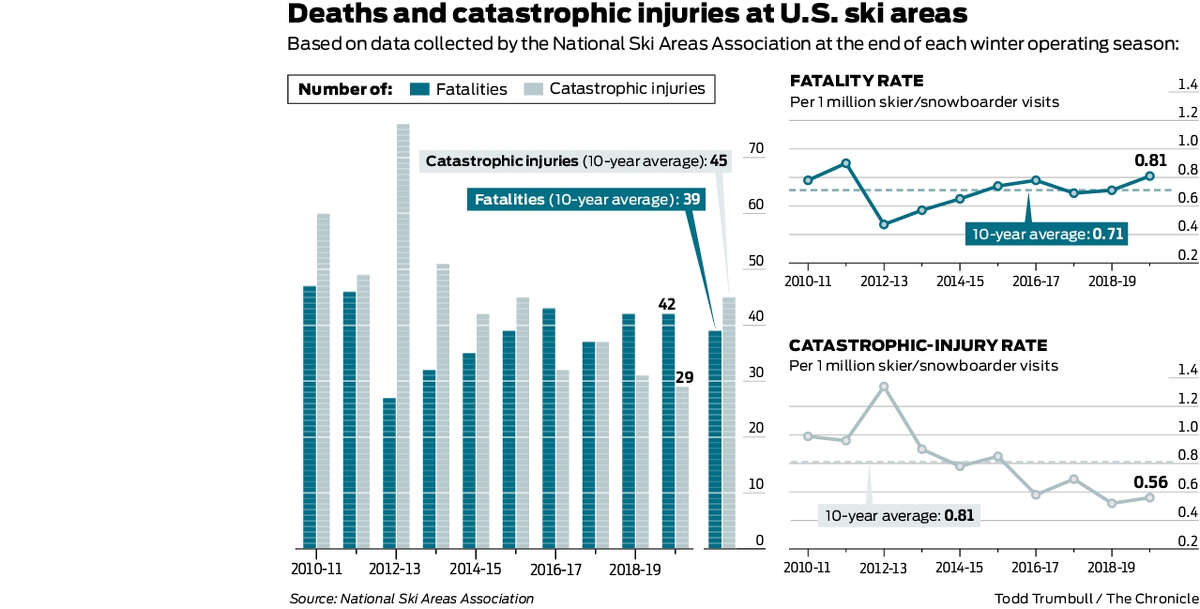

The National Ski Areas Association, which represents about 330 establishments, publishes brief annual reports on deaths and what it calls “catastrophic” injuries. But it doesn’t detail accidents or disclose where they happen.

Industry figures show an average of 39 guests have died at ski areas each of the past 10 years, mainly from collisions with other skiers or fixed objects like trees and chairlift stanchions. Catastrophic injuries are similarly rare, averaging 45 per season since 2010. Broken wrists and heart attacks don’t qualify as catastrophic. Accidents that cause paralysis, loss of a limb or “significant neurological trauma” do, according to the NSAA.

Given that ski areas clock about 55 million skier visits on average per year, the industry maintains the likelihood of dying or suffering a life-changing injury at a resort is exceedingly low.

“The term ‘safety first’ is the mantra of the ski industry,” said NSAA President Kelly Pawlak. “We’re constantly updating and sharing resources with our members so that people see consistent messages and hopefully understand the risks and can be safe.”

Industry safety campaigns have, in fact, changed the way people ski over the years. Helmets, rare on the slopes 20 years ago, are now nearly universal. Messaging around the danger of tree wells, loading onto chairlifts and other issues have also curbed accidents, Pawlak said. Terrain parks, including the one at Bear Valley, are outfitted with placards advising skiers and snowboarders to “start small” and “know your limits.”

Still, people die every year — in crashes, suffocating after falling into tree wells and, in rarer cases, slipping off chairlifts or being buried in avalanches.

The industry emphasizes that an action sport with inherent risks demands personal responsibility, and ski areas commonly waive their liability for accidents and injuries in fine-print disclaimers on their lift passes.

Because ski areas don’t typically announce deaths, they sometimes go unreported altogether. The February accident at Bear Valley, for example, wasn’t written about publicly until a local newspaper article was published in early April.

There have been sporadic efforts to compel ski areas to be more forthcoming about accidents in recent years. Industry critics would like to see resorts create and publish safety plans and incident reports. But the industry has resisted.

“There are no safety standards for the slopes of ski resorts anywhere in this country, including California,” said Dan Gregorie, 72, who founded the research nonprofit SnowSports Safety Foundation in San Francisco in 2007. “If they published safety standards, they would run the risk of being held to those standards. They don’t want to expose themselves to that kind of liability.”

Pressuring the ski industry has been Gregorie’s focus for the past 15 years. Following a career as a doctor and executive in health care management, he formed the nonprofit after his adult daughter died in a fall at Alpine Meadows in North Lake Tahoe in 2006.

“I ran into what many others have run into, a ski resort which was unwilling to give me much of any detail on what happened,” Gregorie said. He contends that it was “a very preventable accident” but he couldn’t persuade the resort to draw skiers’ attention to the hazard. He followed up with an unsuccessful lawsuit.

A person walks through the parking lot at Bear Valley Ski Resort in April.

Max Whittaker / Special to The ChronicleGregorie reasons that more transparency would drive people to ski at the safest areas, allowing the free market to weed out problem resorts or force them to improve.

His efforts have helped stir lawmakers in California and Colorado, the country’s top two skiing destinations, to take up the issue. A survey he produced showed that ski area accidents in California accounted for 11,500 hospital emergency department visits per year, on average, between 2007 and 2011. But legislation proposed in both states has been rejected.

A 2010 California bill that would have mandated ski resorts to post safety plans and produce monthly incident reports was vetoed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, who wrote that it would “place an unnecessary burden on resorts, without assurance of a significant reduction in ski and snowboard-related injuries and fatalities.” (The following year, then-Gov. Jerry Brown shot down a bill that would have required kids to wear helmets at ski areas, calling it an example of “nanny government.”)

After the 2010 defeat, Gregorie and other advocates eventually turned their attention to the country’s skiing capital, Colorado, hoping to score a legislative victory that could serve as a model for other ski states. More than 130 people died at Colorado ski areas between 2006 and 2017, according to an investigation by Summit Daily News, a publication in Colorado’s Front Range. At least 11 more deaths occurred in Colorado this past winter, the Colorado Sun reported.

But a Colorado bill similar to the California legislation died in committee last month after intense debate.

“The ski resorts have been able to hide behind their control of safety data and their political money,” Gregorie said.

Despite the setback, Gregorie is optimistic that the issue could invigorate concerned skiers across the West.

“It’s out there in the public in a way that it’s never been before,” he said.

There is widespread disagreement about the potential costs and benefits of releasing detailed accounts of ski accidents.

“It would create confusion more than anything,” said Michael Reitzell, president of the California Ski Industry Association, because every accident involves countless variables. A skier’s skill level and speed, weather and snow conditions are among many contributing factors.

“The data isn’t going to be understandable to the layperson,” Reitzell said. “They won’t be able to draw conclusions that are factually correct.”

Snowboarders and skiers wait to drop into the terrain park at Bear Valley Ski Resort in April

Max Whittaker / Special to The ChronicleThis is a common industry refrain — that the relevant information is beyond the average skier’s understanding. Also, there’s concern that incident reports could mislead prospective guests and tarnish a ski area’s reputation, Reitzell said.

“If I tell you that there were 10 broken wrists at one ski area and 15 at another, what conclusion do you draw from that?” Reitzell said. “Someone could say, well, obviously Resort A is safer. But that’s not how that works.”

But advocates say that’s exactly the kind of information that could help people make the kind of educated decisions that the ski industry asks of them.

“It’s a shared responsibility,” said Richard Penniman, a skiing safety consultant and retired ski patrol director who lives in Truckee and works with Gregorie on advocacy. “But the onus is on the resorts. People can’t avoid what they can’t see, and they can’t see because resorts aren’t showing them what’s happening. They have all the information, but they keep it pretty close to the vest.”

Pawlak, of the NSAA, said she isn’t convinced that publishing extensive incident reports would help people plan their ski trips or avoid catastrophe.

“People fall, and it sucks, and it’s part of our business,” Pawlak said. “But no matter how much data we give, there are going to be a certain amount of injuries and fatalities.”

In March, two weeks after her husband’s death, Ares traveled to Bear Valley with family members to see where her husband had died.

The resort’s ski patrol leader took her up to the terrain park in a snowmobile. Signs posted at the entry invoked the NSAA’s safety recommendations.

Ares said the ski patroller was kind and respectful and that he described the resort’s efforts to help her husband. She followed up later with an email inquiring as to whether other people have hurt themselves on the Volcano feature where her husband back-flipped — she didn’t receive a reply.

Bear Valley did compile a report on the incident for insurance purposes but didn’t share its findings with Ares and won’t release it publicly, director of operations Schimke said.

“We found that (the Volcano feature) is well within the bounds of what we usually create and what we build and maintain with terrain parks,” he said.

There is widespread disagreement about the risks posed by terrain parks. Reitzell said that there have been seven terrain park fatalities nationwide in the past six seasons but wasn’t sure about the number of injuries.

However, research papers indicate that most terrain parks aren’t optimally designed for skiers and riders to land jumps as smoothly as possible and highlight a risk of spinal injuries that can lead to paralysis.

“The problem is virtually none of the terrain park jumps are designed from a mechanical point of view,” said Mont Hubbard, a retired UC Davis engineering professor who has published several papers on terrain park risks and serves as an expert witness for plaintiffs seeking damages over park injuries. “If they’d been designed in a more careful, protective way, it’s more likely that some of these injuries wouldn’t have occurred at all.”

If Ares were to file a lawsuit, she would likely have to prove that Bear Valley’s protocols contributed to her husband’s accident. She acknowledges that winning a legal battle with a ski resort would be difficult.

Still, she is frustrated that no one can tell her how many people have been hurt on the park feature where her husband died.

“That’s the only thing I want to know,” she said.

Gregory Thomas is the Chronicle’s editor of lifestyle & outdoors. Email: gthomas@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @GregRThomas

"difficult" - Google News

May 05, 2021 at 06:03PM

https://ift.tt/3tj5sQk

Why it’s difficult to get detailed information when skiers die at California resorts - San Francisco Chronicle

"difficult" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VWzYBO

https://ift.tt/3d5eskc

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why it’s difficult to get detailed information when skiers die at California resorts - San Francisco Chronicle"

Post a Comment